- Perspective – November 2022

- Columbus Advert

- Market Intelligence

- Unique Welding Advert

- Industry Analysis

- Industry Insight

- Market Intelligence

- Industry Networks

- Advertorial – NDE

- Webinar Report Back

- Schultz Incorporated Advert

- Case Study

- Professional Profile

- Inox Systems Advert

- Africa Focus

- Member Insight

- Training Focus

- Obituary – Vaughan Davis

- Member Focus

AIR CRASH INVESTIGATION- THE TRAGIC CONSEQUENCES OF MISUNDERSTANDING STAINLESS STEEL

Stainless steel is known for its incredible ability to resist corrosion. However, a skewed focus on a singular aspect of material selection and a lack of understanding of the correct grades of material required for high-stress environments can lead to tragic consequences…

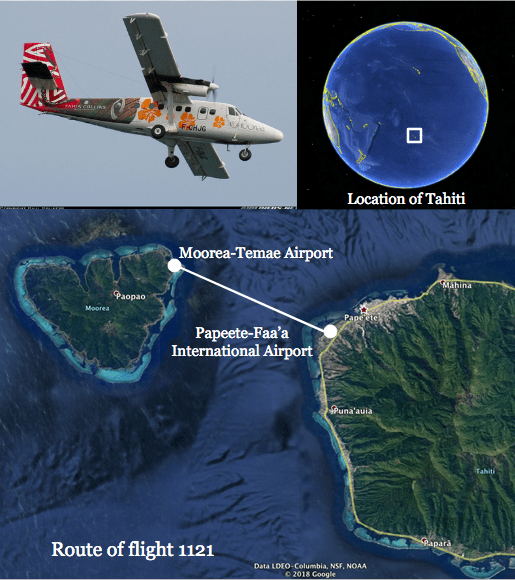

On the 9th of August 2007, one of the shortest flights in the world ended in disaster when a de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter from Air Moorea suddenly plunged into the Pacific Ocean, killing all 20 people on board.

The crash on French Polynesia’s most popular tourist route sparked a year-long investigation that ultimately uncovered multiple threats affecting not just the Twin Otter, but every small plane operating out of a major airport.

Air Moorea was a small air carrier based on the island of Moorea in French Polynesia. It specialised in short commuter flights between the scattered islands of the archipelago using its fleet of four de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter propeller planes, which could carry 19 passengers and one pilot.

Flight 1121 was Air Moorea’s busiest route, from Moorea to Faa’a on the neighbouring island of Tahiti. This flight lasted just seven minutes and Air Moorea ran it more than 40 times per day.

The Twin Otter has fully manual flight controls that are directly connected to the pilot’s yoke via steel cables. The Twin Otter operating this flight had been acquired separately from Air Moorea’s other three aircraft, and there was a small, seemingly insignificant difference between them.

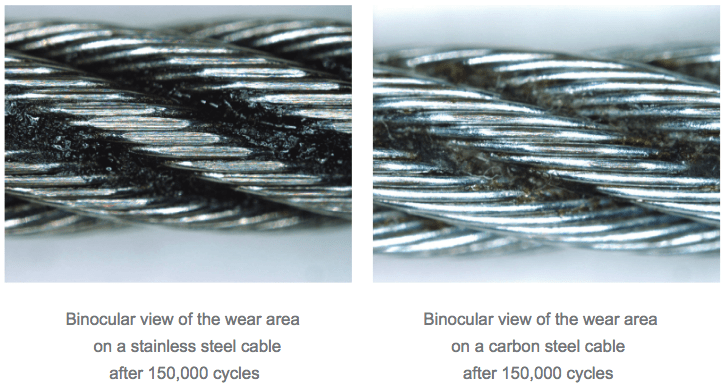

Whereas the other Twin Otters had carbon steel control cables, this Twin Otter had stainless steel control cables. According to the manufacturer, both types were to be treated identically. As a result, Air Moorea had no idea that this plane was any different.

A TRAGIC TRADE OFF

The original reason for using stainless steel was that it suffered much less corrosion than carbon steel. But there was a trade-off. The stainless steel cables suffered more frictional wear than the carbon steel ones. Every time a pilot moved the control surfaces, the cables rubbed against various pulleys and guide holes, causing them to wear down over time.

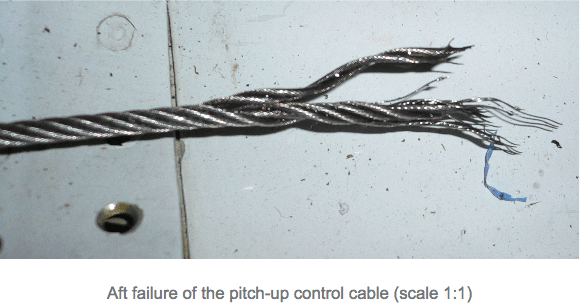

The particular cables of interest in this incident were the elevator cables. The Twin Otter elevator control system consisted of a “pitch up” cable and a “pitch down” cable which formed a closed loop, allowing the elevators to move up or down when the appropriate cable was in tension. On the Air Moorea Twin Otter with stainless steel cables, the elevator pitch-up cable started wearing against a guide hole, a point where the cable passes through the aeroplane’s internal structure. The cable is made up of seven interwoven strands, each of which is composed of 19 individual wires.

By August 2007, 72 of the 133 total wires had worn through. Nevertheless, sufficient strength remained for the cable to continue bearing all the normal loads associated with flight. That is until an unfortunate coincidence pushed it to the breaking point.

AN UNFORTUNATE COINCIDENCE

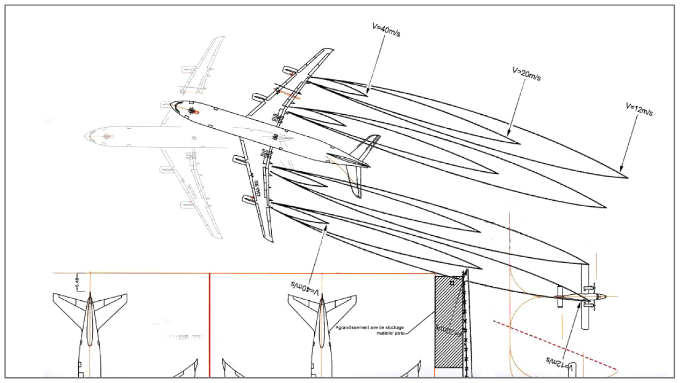

The night before Flight 1121, the Twin Otter was parked at Papeete-Faa’a International Airport. The berth where Air Moorea stored its Twin Otters, was located close to a gate used by Air France’s body Airbus A340s. When jet engines spool up, they bombard everything behind them with a powerful burst of wind called a jet blast. As it turned out, if an A340 pushed back slightly too far from this gate, the planes parked in the outermost berth could be struck by its jet blast, subjecting them to winds of up to 162kph.It is highly likely that the Twin Otter with the badly worn elevator cable was struck by just such a blast that night. The jet blast placed enormous strain on the elevator, which transferred the stress to the cable.

However, the cable could not move to alleviate the stress because it was held in place by the gust lock - a device that prevents wind from moving the elevators while the plane is parked.

A normal cable would not be seriously damaged by such a blast, but in this case, the severely worn cable had a reduced ability to withstand the strain, and several strands snapped in the worn area. The elevator pitch-up cable was left with just one of its seven original strands intact.

UNSEEN DAMAGE

That last strand was enough for the elevators to continue functioning until shortly before noon the next day when the Twin Otter took on 19 passengers for Flight 1121 from Moorea back to Tahiti.

Before take-off, the pilot performed the standard elevator checks, and the elevators functioned normally. Flight 1121 was cleared for take-off and took to the sky shortly after midday.

About halfway to the flight’s cruising altitude of 600 feet, the pilot retracted the flaps, which increase lift on take-off and landing.

The tendency of the Twin Otter with the flaps retracted was to pitch down, so when he retracted the flaps, the pilot naturally pulled up with the elevators to continue climbing. This was the largest force applied to the critically damaged elevator pitch-up cable that day, and it proved incapable of handling the stress. The pitch-up cable snapped, causing the aeroplane to succumb to its natural desire to pitch down.

Just eleven seconds after the cable broke, Air Moorea Flight 1121 plunged nose-first into the channel between Moorea and Tahiti, destroying the aircraft and instantly killing all 20 people on board. The wreckage came to rest on a steep underwater slope 700 meters below the surface, and a specialised search vessel had to recover the plane.

It was not until several weeks after the crash that investigators finally saw the elevator cables and noticed the damage. Even then, the full story was far from obvious. Tests showed that the wear on the cable was by itself insufficient to cause its failure. Without the coincidental jet blast encounter, the cable would likely have lasted until the next inspection, at which point it would have been replaced.

A FATAL LACK OF UNDERSTANDING

The investigators also found numerous points at which the accident could have been prevented. For example, the parking area at Faa’a used to have a fence to protect parked planes from the jet blast effect, but it had been taken down in 2004 to make way for a new taxiway.

The accident could have been prevented. For example, the parking area at Faa’a used to have a fence to protect parked planes from the jet blast effect, but it had been taken down in 2004 to make way for a new taxiway.

Most importantly, the lack of separate guidance from the manufacturer regarding stainless steel control cables represented a blatant safety deficiency. The original manufacturer, de Havilland Canada, had long since given up the aircraft’s production rights to Canadian aircraft producer Viking Air. Unfortunately, Viking Air had not conducted any wear rate tests on stainless steel cables, apparently assuming that the existing replacement interval would be sufficient.

Air Moorea regularly inspected its control cables too, but because the damage to the elevator pitch-up cable was in a location that was difficult to see, it was not discovered in time. It was clear that a system based on finding and replacing damaged cables during routine inspections was insufficient, and that a shorter mandatory replacement interval was necessary. If Air Moorea had replaced its stainless steel cables on this Twin Otter at the same interval as airlines that knew about the problem, the crash would never have happened.

A PREVENTABLE CRASH

A final tragic element to the story was that, had the pilot known what he was facing, he could have saved the plane. Live tests in a real Twin Otter showed that if the pilot had used the stabiliser trim to pitch the plane up within three seconds of the failure, Flight 1121 would have recovered before hitting the water. But it was unreasonable to expect him to be able to act so quickly, especially considering that he had not been trained on how to react to failures of the primary flight controls.

After narrowing down the cause, the French Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety learned of similar wear on other Twin Otters with stainless steel control cables and issued an urgent recommendation to Transport Canada and the European Aviation Safety Agency calling for inspections of all such cables.

In its final report, the BEA took this one step further, recommending that stainless steel control cables be banned on the Twin Otter until research into wear was performed and new maintenance guidelines were created.

It also called for studies of other aircraft with stainless steel control cables to see if they too could be vulnerable. They also recommended that the French Directorate General for Civil Aviation encourages communication between airlines and manufacturers regarding recurring maintenance issues and that airports be informed of the risks of jet blasts to parked aircraft.

**Pictures courtesy of https://admiralcloudberg.medium.com/the-crash-of-air-moorea-flight-1121-analysis-4cbc6ea283d3